Why Dennis Potter matters….

In TV, that most significant and influential art form of the later 20th century, one of its most significant figures is Dennis Potter. One of a handful of British writers, producers and directors who from the early 1960's onwards pushed at the boundaries of what television drama could do he remains an influence on many of today's most significant television writers. Dennis Potter most certainly still matters!

With a written archive and exhibition now established in the Forest of Dean, cataloguing of his papers is now almost complete. This rich resource has much more to tell us all about the man and his work.

This website aims to act as a resource for scholars, fans and enthusiasts, a focus for new events, research and publications. Thanks you to all of those who have contributed to the site, in particular to the advice and support of Dr Joanne Garde-Hansen, Dr Hannah Grist, and Prof John Cook.

Jason Griffiths

University of Gloucestershire

April 2016

In TV, that most significant and influential art form of the later 20th century, one of its most significant figures is Dennis Potter. One of a handful of British writers, producers and directors who from the early 1960's onwards pushed at the boundaries of what television drama could do he remains an influence on many of today's most significant television writers. Dennis Potter most certainly still matters!

With a written archive and exhibition now established in the Forest of Dean, cataloguing of his papers is now almost complete. This rich resource has much more to tell us all about the man and his work.

This website aims to act as a resource for scholars, fans and enthusiasts, a focus for new events, research and publications. Thanks you to all of those who have contributed to the site, in particular to the advice and support of Dr Joanne Garde-Hansen, Dr Hannah Grist, and Prof John Cook.

Jason Griffiths

University of Gloucestershire

April 2016

Fairytale in the Forest: The Dennis Potter Archive Opens

June 29 2013 was a very significant day, as well as a very interesting one, for me. A Dennis Potter archive in the Forest of Dean. An almost complete collection of the writer's notebooks and handwritten manuscripts of his most famous scripts. If you had said that to me over twenty five years ago when, awed by the first transmissions of the BBC TV version of 'The Singing Detective', I asked myself as an undergraduate student 'Wouldn't it be great to do academic research on Dennis Potter ?' (followed almost immediately by an amazed 'Why has no-one else ever done this before ?'), I would have said 'A Potter archive ?' 'Surely beyond the bounds of possibility ?' When, as a PhD student in 1990, I cheekily asked Dennis Potter himself if I could get access to drafts of his manuscripts, he, understandably for a working writer, deflected protectively: 'I destroy things', he told me. 'Rip, rip, rip'. In fact, as we now know, he always kept, at the very least, the final handwritten copies of his old manuscript materials, each carefully filed away for posterity; each the product of a highly organised and organising mind. In 2004, ten years after Potter's death, when, by this time I was a full-time media studies academic and published Potter scholar, you had asked me about the possibility of a Potter archive - I would have said something like it is what needs to happen if 'Potter Studies' is to have a future and Potter's artistic achievements are not to fade into obscurity and be forgotten by future generations, but how is it going to happen ? By this stage I was aware of the existence of the manuscripts but they were the property of an Estate understandably protective after the setback of an 'official' biography which went so badly wrong after salacious details were taken out of context and sold, pre-publication, to the newspapers. And an archive in the Forest of Dean ? That would be the proper and fitting place for it, but could it really happen ? One could dream but surely this was destined to be just another fairytale?

But 2004 was the year of 'Voices of the Forest' when, with the blessing of the Potter family, the Foresters themselves got together to celebrate their famous son on the tenth anniversary of his passing and with that came new hope and possibility. When, at the end of that very successful event and in conversation with one of its principal organisers, Jason Griffiths, I drew his attention to the existence of the manuscripts and we first discussed the question of 'what if...?', he could instantly see the possibilities and the tremendous benefits for the Forest community of having the papers within their midst. That night a little spark was lit. But agreeing 'Wouldn't it be great if...?' was a long way from actually being able to make it happen. So many potential obstacles; so many lurking spanners in the works waiting to get in the way of what could have been, in the end, a rather crazy romantic dream. It has taken nine years and an awful lot of hard work and dedication by many people in the Forest of Dean and beyond to make the fairytale a reality but on June 29, in defiance of the logistical odds, it finally happened and the Potter archive officially opened in the Forest. And what an interesting and stimulating day of talks and events that day was. All of us involved with it can only hope that the late Dennis Potter himself would have been pleased - and moved. The boy who maybe always felt himself to be an outcast from the Forest and from the Forest people he so clearly loved finally has had his chance to return home.

John R Cook

Professor of Media, Glasgow Caledonian University

23rd August 2013

contact John

June 29 2013 was a very significant day, as well as a very interesting one, for me. A Dennis Potter archive in the Forest of Dean. An almost complete collection of the writer's notebooks and handwritten manuscripts of his most famous scripts. If you had said that to me over twenty five years ago when, awed by the first transmissions of the BBC TV version of 'The Singing Detective', I asked myself as an undergraduate student 'Wouldn't it be great to do academic research on Dennis Potter ?' (followed almost immediately by an amazed 'Why has no-one else ever done this before ?'), I would have said 'A Potter archive ?' 'Surely beyond the bounds of possibility ?' When, as a PhD student in 1990, I cheekily asked Dennis Potter himself if I could get access to drafts of his manuscripts, he, understandably for a working writer, deflected protectively: 'I destroy things', he told me. 'Rip, rip, rip'. In fact, as we now know, he always kept, at the very least, the final handwritten copies of his old manuscript materials, each carefully filed away for posterity; each the product of a highly organised and organising mind. In 2004, ten years after Potter's death, when, by this time I was a full-time media studies academic and published Potter scholar, you had asked me about the possibility of a Potter archive - I would have said something like it is what needs to happen if 'Potter Studies' is to have a future and Potter's artistic achievements are not to fade into obscurity and be forgotten by future generations, but how is it going to happen ? By this stage I was aware of the existence of the manuscripts but they were the property of an Estate understandably protective after the setback of an 'official' biography which went so badly wrong after salacious details were taken out of context and sold, pre-publication, to the newspapers. And an archive in the Forest of Dean ? That would be the proper and fitting place for it, but could it really happen ? One could dream but surely this was destined to be just another fairytale?

But 2004 was the year of 'Voices of the Forest' when, with the blessing of the Potter family, the Foresters themselves got together to celebrate their famous son on the tenth anniversary of his passing and with that came new hope and possibility. When, at the end of that very successful event and in conversation with one of its principal organisers, Jason Griffiths, I drew his attention to the existence of the manuscripts and we first discussed the question of 'what if...?', he could instantly see the possibilities and the tremendous benefits for the Forest community of having the papers within their midst. That night a little spark was lit. But agreeing 'Wouldn't it be great if...?' was a long way from actually being able to make it happen. So many potential obstacles; so many lurking spanners in the works waiting to get in the way of what could have been, in the end, a rather crazy romantic dream. It has taken nine years and an awful lot of hard work and dedication by many people in the Forest of Dean and beyond to make the fairytale a reality but on June 29, in defiance of the logistical odds, it finally happened and the Potter archive officially opened in the Forest. And what an interesting and stimulating day of talks and events that day was. All of us involved with it can only hope that the late Dennis Potter himself would have been pleased - and moved. The boy who maybe always felt himself to be an outcast from the Forest and from the Forest people he so clearly loved finally has had his chance to return home.

John R Cook

Professor of Media, Glasgow Caledonian University

23rd August 2013

contact John

From Collective Memory of Dennis Potter to Collecting Memories of Dennis Potter

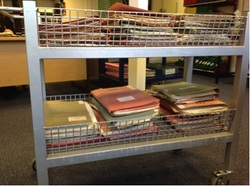

A photograph of a sample of an official archive: Dennis Potter production files at the BBC Written Archives, Caversham, UK. Pre-1979, these files are irregularly opened by researchers. But what does it mean when the written archive of Potter’s scripts, notes and unpublished works is purchased by the Dean Heritage Centre and housed in the Forest of Dean, Gloucestershire?

It would be easy to leave Dennis Potter’s work in television’s past. To take a historical approach to television would consign his creativity to a period of British television history concerned with ‘quality’ and an increasingly commercialised and deregulated media landscape from 1980s-1990s. Potter’s final interview with Melvyn Bragg in 1994, available on YouTube is oft-cited for his reference to Rupert Murdoch as the name of his ‘cancer’, and The Singing Detective is re-energised both online and on BBC4 (the channel of TV’s own past) as a ‘classic’. In terms of legacy, just these examples suggest we have only a partial understanding of where television as heritage resides and by whom it is reconstructed. For the institutions, the businesses and all the stakeholders in television’s past, a collective memory is instrumentalized as culturally, commercially and professionally valued. This is the UK’s creative heritage. Sometimes this accords with what audiences have found memorable, often not. Sometimes it remembers under-valued works, mostly there is darkness waiting for researchers (academic/production/fans) to shine a light. Or, at least that’s how the mythology of TV archives works.

Television as a collective memory is crucial notion if past work is to retain its ‘value’ in the future, if the archive is to be preserved, if the production values are to be remembered. These value systems frame the ‘official memory’ of Potter’s works, produced by professionals (from TV to archives to literary agents), and includes those memories deemed to be of archival value. It is on this basis that the Dean Heritage Centre in the Forest of Dean had the leverage to make the case that Potter’s written archive was valuable but, and this is important, that its cultural value could be renegotiated in terms of who gets to remember. Not producers but audiences and below the line production workers rooted in the region that is textually represented.

Television’s past, the past of television has resided and does reside in official archives and on (semi) official channels: the BBC Written Archives at Caversham; ITN Source; the BBC’s broadcast archive at Perivale; the BFI; BBC4, UKGold, YouTube or the National Media Museum. What is valued is archived. What has value at a moment in time is preserved for future use (patchily by the BBC up until 1978). This value is productive, economic and resource-intensive. Experts, professionals and even academics continually reproduce it: they decide what is to be recalled, remembered, re-run, rethought and, therefore, inherited. I do not exclude academic scholarship from this process of cultural inheritance. The implicit cultural policy of academic work on television means that intentionally or not, Potter’s work tends to get ‘periodised’ as belonging to a certain ‘era’ (internally in its representations of the 1950s) and externally in its production context of the emergence of a type of ‘creative drama’ only seen as possible at a particular time. What I mean here is that academic research of television cannot forget itself as a valuable player in what ‘it’ is choosing to remember as part of a collective memory of television’s past. ‘The ontology of memory’ says Jeffrey K Olick ‘does not exclude the possibility that different rememberers are valued differently in the group, that the memories of some command more attention than those of others’ (2011, 225). Hence, he says rather than a collective memory, let’s think about a collected memory.

With this in mind, the Dennis Potter Heritage Project was designed to show just what happens when memories of Potter’s work are collected, and collected from the places and spaces in which his TV productions were filmed: not the studios but the region, not in discussions with Kenth Trodd, but in the trees, landscapes, houses and community spaces that he was attempting to represent on screen: the Forest of Dean. The danger in constructing a ‘Forest Potter’ as opposed to a ‘London Potter’ is that the regional and the urban remain separate and uncontested. I shall ruminate on this notion of TV as non-urban (suburban, rural, regional) at a later date. For now, by moving a valuable archive back to the Forest, the idea was that television heritage and television’s legacy lies just as much in ‘different rememberers’ whose memories have not been deemed valuable to preserve: the memories of fans, audiences, production workers and the local community. This reflects something important being conveyed about ‘memory’ and remembering in Potter’s work: what we remember, what we forget, flashbulb memories, competitive memories, repressed memories, strategic forgetting in order to move forward. Anyone wishing to find out more about the project can visit the Dean Heritage Centre, read blog postings here or look out for future publications.

As a final point. It is interesting that much of the scholarship on the TV audience has come from female scholars, and it is interesting again that much of the scholarship on Potter has come from male scholars. Potter’s heritage has been masculinised: industrial heritage, the roman à clef of pseudo-autobiography, women’s betrayal of the family, ventures into sci-fi and the representation of degrading sexuality. The anti-woman label is sticky. There is little audience research of Potter: as if his work and the domestic spaces of viewing are antagonistic to one another. There is little research on women viewers of Potter’s dramas: this can only happen now through memory work. Yet, by resituating Potter’s work back in the Forest of Dean, in a different kind of institution, community-focused, regional and off the beaten track, means that researchers of television are required to double check their approach to television’s past. Interviewing female audience members on their strong and abiding memories of Potter’s productions in the Forest, how the childhood in Blue Remembered Hills, felt just like how their memories of ‘serious play’ in the Forest, how the music of Pennies from Heaven bound places and cultures together and how Potter’s representations of sexuality were both memorable and challenging, as young women recalled generational arguments about propriety. To return to community, region and below the line production memories, values different rememberers and means that Potter matters not because of well-worn academic discussions of quality versus commerciality, but because he reveals that memorable television is less about ‘what’ is remembered and more about ‘who’ is doing the remembering. In his 2003 article ‘Some Sense of Time: Remembering Television’ Jerome Bourdon says that: ‘What is remembered is not programmes but interaction with TV’ (2003, 12).

Dr Joanne Garde-Hansen

Associate Professor in Culture, Media and Communication, University of Warwick

29th August 2013

contact Jo

A photograph of a sample of an official archive: Dennis Potter production files at the BBC Written Archives, Caversham, UK. Pre-1979, these files are irregularly opened by researchers. But what does it mean when the written archive of Potter’s scripts, notes and unpublished works is purchased by the Dean Heritage Centre and housed in the Forest of Dean, Gloucestershire?

It would be easy to leave Dennis Potter’s work in television’s past. To take a historical approach to television would consign his creativity to a period of British television history concerned with ‘quality’ and an increasingly commercialised and deregulated media landscape from 1980s-1990s. Potter’s final interview with Melvyn Bragg in 1994, available on YouTube is oft-cited for his reference to Rupert Murdoch as the name of his ‘cancer’, and The Singing Detective is re-energised both online and on BBC4 (the channel of TV’s own past) as a ‘classic’. In terms of legacy, just these examples suggest we have only a partial understanding of where television as heritage resides and by whom it is reconstructed. For the institutions, the businesses and all the stakeholders in television’s past, a collective memory is instrumentalized as culturally, commercially and professionally valued. This is the UK’s creative heritage. Sometimes this accords with what audiences have found memorable, often not. Sometimes it remembers under-valued works, mostly there is darkness waiting for researchers (academic/production/fans) to shine a light. Or, at least that’s how the mythology of TV archives works.

Television as a collective memory is crucial notion if past work is to retain its ‘value’ in the future, if the archive is to be preserved, if the production values are to be remembered. These value systems frame the ‘official memory’ of Potter’s works, produced by professionals (from TV to archives to literary agents), and includes those memories deemed to be of archival value. It is on this basis that the Dean Heritage Centre in the Forest of Dean had the leverage to make the case that Potter’s written archive was valuable but, and this is important, that its cultural value could be renegotiated in terms of who gets to remember. Not producers but audiences and below the line production workers rooted in the region that is textually represented.

Television’s past, the past of television has resided and does reside in official archives and on (semi) official channels: the BBC Written Archives at Caversham; ITN Source; the BBC’s broadcast archive at Perivale; the BFI; BBC4, UKGold, YouTube or the National Media Museum. What is valued is archived. What has value at a moment in time is preserved for future use (patchily by the BBC up until 1978). This value is productive, economic and resource-intensive. Experts, professionals and even academics continually reproduce it: they decide what is to be recalled, remembered, re-run, rethought and, therefore, inherited. I do not exclude academic scholarship from this process of cultural inheritance. The implicit cultural policy of academic work on television means that intentionally or not, Potter’s work tends to get ‘periodised’ as belonging to a certain ‘era’ (internally in its representations of the 1950s) and externally in its production context of the emergence of a type of ‘creative drama’ only seen as possible at a particular time. What I mean here is that academic research of television cannot forget itself as a valuable player in what ‘it’ is choosing to remember as part of a collective memory of television’s past. ‘The ontology of memory’ says Jeffrey K Olick ‘does not exclude the possibility that different rememberers are valued differently in the group, that the memories of some command more attention than those of others’ (2011, 225). Hence, he says rather than a collective memory, let’s think about a collected memory.

With this in mind, the Dennis Potter Heritage Project was designed to show just what happens when memories of Potter’s work are collected, and collected from the places and spaces in which his TV productions were filmed: not the studios but the region, not in discussions with Kenth Trodd, but in the trees, landscapes, houses and community spaces that he was attempting to represent on screen: the Forest of Dean. The danger in constructing a ‘Forest Potter’ as opposed to a ‘London Potter’ is that the regional and the urban remain separate and uncontested. I shall ruminate on this notion of TV as non-urban (suburban, rural, regional) at a later date. For now, by moving a valuable archive back to the Forest, the idea was that television heritage and television’s legacy lies just as much in ‘different rememberers’ whose memories have not been deemed valuable to preserve: the memories of fans, audiences, production workers and the local community. This reflects something important being conveyed about ‘memory’ and remembering in Potter’s work: what we remember, what we forget, flashbulb memories, competitive memories, repressed memories, strategic forgetting in order to move forward. Anyone wishing to find out more about the project can visit the Dean Heritage Centre, read blog postings here or look out for future publications.

As a final point. It is interesting that much of the scholarship on the TV audience has come from female scholars, and it is interesting again that much of the scholarship on Potter has come from male scholars. Potter’s heritage has been masculinised: industrial heritage, the roman à clef of pseudo-autobiography, women’s betrayal of the family, ventures into sci-fi and the representation of degrading sexuality. The anti-woman label is sticky. There is little audience research of Potter: as if his work and the domestic spaces of viewing are antagonistic to one another. There is little research on women viewers of Potter’s dramas: this can only happen now through memory work. Yet, by resituating Potter’s work back in the Forest of Dean, in a different kind of institution, community-focused, regional and off the beaten track, means that researchers of television are required to double check their approach to television’s past. Interviewing female audience members on their strong and abiding memories of Potter’s productions in the Forest, how the childhood in Blue Remembered Hills, felt just like how their memories of ‘serious play’ in the Forest, how the music of Pennies from Heaven bound places and cultures together and how Potter’s representations of sexuality were both memorable and challenging, as young women recalled generational arguments about propriety. To return to community, region and below the line production memories, values different rememberers and means that Potter matters not because of well-worn academic discussions of quality versus commerciality, but because he reveals that memorable television is less about ‘what’ is remembered and more about ‘who’ is doing the remembering. In his 2003 article ‘Some Sense of Time: Remembering Television’ Jerome Bourdon says that: ‘What is remembered is not programmes but interaction with TV’ (2003, 12).

Dr Joanne Garde-Hansen

Associate Professor in Culture, Media and Communication, University of Warwick

29th August 2013

contact Jo

Working with Potter's Work

The Potter Archive is an important acquisition for the Dean Heritage Centre and the Forest of Dean as a whole. I believe that this project will leave a lasting legacy, and the archive will continue to increase in local, national and international importance.

The Dennis Potter Archive had not been previously catalogued, which meant that there was no record of what the archive contained. Once it has been fully catalogued, members of the public will be able to book an appointment to view this vast collection of Potter’s work. There are in excess of 370 documents within the Potter Archive, which includes multiple draft manuscripts – typed and handwritten - published and unpublished works, production notes, and articles for television reviews. Although the archive is by no means a complete record of Potter’s work (some produced plays do not appear) it represents some of British television drama’s most significant ever productions.

Many works have numerous drafts and seem to have been continuously reworked. This includes Potter’s New Statesman article on the Aberfan disaster, and his version of Charles Dickens’s The Mystery of Edwin Drood. Many works began life under a different title, and can be seen to be significantly different to the final completed work, for example, an early draft of The Changing Forest is titled Blessed was the Eye, and an early version of Paper Roses is entitled Scissors and Paste and the plot is different to the final version. Perhaps most exciting of all there are a number of documents that are, to quote John Cook, “previously unknown in the Potter canon”.

Phillippa Turner

Collections Officer at The Dean Heritage Centre, home of The Dennis Potter Archive & Exhibition

4th September 2013

The Potter Archive is an important acquisition for the Dean Heritage Centre and the Forest of Dean as a whole. I believe that this project will leave a lasting legacy, and the archive will continue to increase in local, national and international importance.

The Dennis Potter Archive had not been previously catalogued, which meant that there was no record of what the archive contained. Once it has been fully catalogued, members of the public will be able to book an appointment to view this vast collection of Potter’s work. There are in excess of 370 documents within the Potter Archive, which includes multiple draft manuscripts – typed and handwritten - published and unpublished works, production notes, and articles for television reviews. Although the archive is by no means a complete record of Potter’s work (some produced plays do not appear) it represents some of British television drama’s most significant ever productions.

Many works have numerous drafts and seem to have been continuously reworked. This includes Potter’s New Statesman article on the Aberfan disaster, and his version of Charles Dickens’s The Mystery of Edwin Drood. Many works began life under a different title, and can be seen to be significantly different to the final completed work, for example, an early draft of The Changing Forest is titled Blessed was the Eye, and an early version of Paper Roses is entitled Scissors and Paste and the plot is different to the final version. Perhaps most exciting of all there are a number of documents that are, to quote John Cook, “previously unknown in the Potter canon”.

Phillippa Turner

Collections Officer at The Dean Heritage Centre, home of The Dennis Potter Archive & Exhibition

4th September 2013